This review was commissioned by Paper Visual Art Journal for the publication ‘Blueprint’ launched in October 2015.

Group Show

‘Psychic Lighthouse’

The Model, Sligo

12 June–30 August 2015

Susan MacWilliam, still from HD video installation, ‘An Answer is Expected’, 65 mins, 2014

Maybe it’s the zeitgeist, but while the Model is brightening up on many fronts, the galleries themselves – currently painted black – have become distinctly crepuscular. This group exhibition, curated by Emer McGarry, is the Model’s second show – following Things Go Dark in 2014 – dealing with notions of the sublime, the uncanny, and things that go bump in the night. On the 150th anniversary of his birth, W. B. Yeats is also a spirit of the times. Providing a touchstone for the exhibition’s themes, the visionary poet and enthusiastic occultist, vexed within his Drumcliffe bed, casts a cold, unblinking eye.

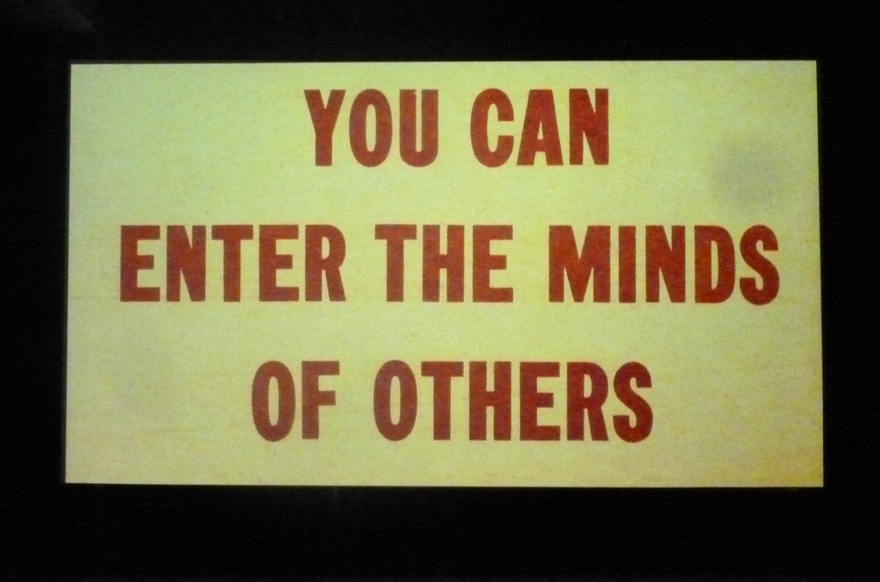

At the exhibition entrance a neon sign asserts, ‘An answer is expected.’ This artwork by Susan MacWilliam reads like good advice. ‘Pay attention’, it appears to say, ‘there’ll be questions later!’ MacWilliam’s interrogation of the supernatural has been primarily conducted through a medium that seems naturally akin to it – the ghost-making apparatus of the camera. Her video documentary about leading parapsychologist Dr. J. B. Rhine (1895–1980) examines ESP (Extra Sensory Perception) and the application of scientific methods to questions of belief. It’s sixty-five minutes long. About ten minutes in I heard an interviewee say, ‘Anyone doing anything is a believer in what they’re doing; otherwise they wouldn’t do it.’ In the next room Book Spheres (2014) is a collection of paper-covered balls, carefully made from recycled book covers, their stylish typographies signaling worlds of arcane knowledge. MacWilliam recognises writing as a kind of telepathy, and the book as its most iconic medium. The symbolic weight of these literary planets, their gravitational pull, contrasts nicely with the artist’s light touch. Glowing resolutely on the opposite wall her second sign asks, ‘Where are the dead?’ The curt enquiry made me self-conscious, ‘You talkin’ to me?’

‘Where is Madame Blavatsky?’ was another question it seemed necessary to ask. Hovering between two chairs, a wooden and fibreglass effigy of the founder of the Theosophical Society must have made a dramatic impact. By the time I arrived, however, this piece by Polish artist Goshka Macuga had been unexpectedly removed (spirited away?) and replaced by another life-sized figure, namely, Cesare, the marauding somnambulist from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Prone and ashen-faced, the stretched-out figure is dressed entirely in black, with a white ‘X’ inscribed across his narrow chest. Is he dead or dreaming? Alone with him in the small room, I had the uneasy feeling his eyes might open at any minute, and he would rise up like a slimline Frankenstein.

Goshka Maguga ‘The Somnambulist’ 2006

Goshka Maguga ‘The Somnambulist’ 2006

Deirdre McKenna’s Murmur (2014) is a trio of small brass medallions. Holding images of ghostly veils floating in stygian voids, they represent ‘the thin veil that exists between the metaphysical world and the world of surfaces’. [1] They also allude to ‘ghost marriages’, ghoulish ceremonies in which a deceased woman is exhumed and reburied next to a recently deceased bachelor. In some parts of China, and there are variations elsewhere, this practice is believed to forestall loneliness after death. Seductive forms holding uncomfortable truths are also present in the work of Maria Loboda, the second Polish artist in the show. Her Curious and Cold Epicurean Young Ladies (2011) is a silver flask lined with platinum. (Loboda’s title is an encrypted reference to the character Anna in Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. Deciphering Loboda’s code is part of the fun.) The small, disc-like flask looks like a closed pocket watch, hanging from the ceiling on a thin chain. Spot-lit against the dark wall, it contains hydrogen, the lightest and most abundant of the natural elements. Platinum is a catalyst for explosive reactions between hydrogen and oxygen. This innocent-looking object is a silently ticking bomb. Loboda’s second work is a complex installation titled Four or Five Manifestations of a Nightmare. The arrangement of objects – broken candles, a shrouded obelisk – seems glibly Freudian, its staging better suited to a drama-school séance than a genuine evocation of the unconscious.

Unconscious desires, and how they might sabotage conscious aspiration, is a major theme in Andrei Tarkovsky’s famous 1979 film, Stalker. Identified simply as ‘Professor’, ‘Writer’, and the eponymous ‘Stalker’, the film’s protagonists enter ‘the Zone’ to alternatively destroy, cast doubt on, or worship its central enigma: the magically protected ‘Room’. Stephen Rennicks’s Journey to an Unknowable Place (2015) adopts Tarkovsky’s meandering style, ambling through Sligo’s Hazelwood (the same leafy demesne of ‘brightening air’ made famous by Yeats) and into an abandoned factory nearby. An artwork needs to supersede its model, but Stalker is a hard act to follow. Part of a larger project, The Zone Does Not Exist, Rennicks’s travelogue, in drones of crumbling dread, conjures up the mood of Tarkovsky but with little sense of the filmmaker’s substance. The ‘Zone’ is an unforgiving place.

In previous projects such as An Exercise in Seeing and Metaphysical Longings, Clodagh Emoe has upset the viewing protocols of exhibition environments by turning the viewers attention within. At the Model, a video projection of a large group of people looking directly into the camera, We Are and Are Not (2015), continues this play with the dynamics of seeing. Deliberately breaking a cardinal rule of the cinema, Emoe’s crowd watches us watching them. It is reminiscent of Gillian Wearing’s 60 Minutes of Silence (1996), but unlike that bright and twitchy group portrait, Emoe’s figures peer out from an obfuscating gloom. We are implicated in a reciprocal gaze with this silent crowd as they shuffle, scratch, and yawn their way through fifteen minutes of fame, but because we can’t see them very clearly, it’s difficult to care much about them. A work of two parts, the second, live element of We Are and Are Not will include a screening to an audience in an undisclosed location in the Sligo countryside. This conclusion is not available to the gallery audience. We are left in want of the sequel.

‘Drunken psychic and unconscionable necromancer’ is not everyone’s idea of the perfect calling card. But for the eminent Elizabethan John Dee, these qualifications made Edward Kelly just the man for the job. Dee wanted to commune with the angels and Kelly – crop-eared following punishment for forgery – had the knack; his dubious history would be tolerated for heaven’s sake! Exhibited in the British Museum, the obsidian stone, or ‘black mirror’, the pair used as a divining glass is about the size and shape of a table-tennis bat. Joachim Koester’s black-and-white photograph The Magic Mirror of John Dee (2006) shows only a smooth black surface with an irregular pattern of fine white scratches. Resembling a mezzotint by Vija Celmins, the image also has something of Celmin’s intentionally ambiguous scale. Is this a close-up of the famous stone, its surface showing signs of age, or is it a celestial vision, showing the movement of stars in the heavens? Typical of Koester’s work, this conjuring of physical ambiguities with a metaphysical backstory lends the ostensibly ordinary a magic of its own.

On the way to the station, a giant mural of Yeats looked down from a gable end. Shifting as I passed, the clouds released a chink of light, a glint in the poet’s eye. ‘An answer is expected,’ it seemed to say. ‘You talkin’ to me?’ Psychic Lighthouse is an enjoyably theatrical and thought-provoking show but I left Sligo feeling no more (or less) psychically disturbed than before, unsure if its promise of ‘ritual, spiritualism, and esoteric practices’ had really managed to get under my skin.

John Graham, 2015

[1] Quoted from the exhibition wall text.