Naomi Sex commissioned me to write a response to this event staged at the end of her six-month residency at IMMA. The text was originally published by ‘Shower of Kunst’ in March 2015.

‘6IX Degrees’ at IMMA

Curator, Naomi Sex / Artist, Alan-James Burns / Curator, Maysia Wieckiewicz-Carroll / Artist, Linda Quinlan / Curator, Sarah Pierce / Artists Jan Verwoert and Federica Bueti.

Conceived and facilitated by Naomi Sex

Irish Museum of Modern Art

4pm – 7pm, 13 December 2014

“I believe that the imagination is the passport we create to take us into the real world”.

Paul ‘Poitier’, Six Degrees of Separation, John Guare

By 4pm the winter light was already leaving the courtyard separating the artists’ studios from the museum’s main building. Towards the courtyard’s darkest end, where the line of old coach-houses begins, Studios 3A and 3B leaked fluorescence into an expanding pool, brightening – as the natural light faded – around the entrance to the evening’s events.

‘6ix Degrees’ borrowed its title from the theory that everyone in the world is connected to everyone else by a chain of no more than six acquaintances. Expounded by the Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy, it entered a wider consciousness with the appearance in 1990 of John Guare’s Broadway hit, Six Degrees of Separation. (1) Though the theory has gained a wide appeal, the appeal for Sex (how else can I say that?) was not to apply its premise exactly, but to use it as a convenient launch pad for her project “…harnessing the connections and closeness in the Irish art world and beyond.” (2) The small-scale of the Irish art world means that degrees of separation rarely extend to six. That ‘beyond’ is significant, not only in the sense of including artists from outside of Ireland, but also in the indication that harnessing the closeness of local scenes need not limit artistic perspectives.

Art tends to have a central axis – the individual artist – around which it grows and develops. An interesting aspect of 6ix Degrees is that its originator did not adopt a central role but positioned herself at the beginning of a line projecting outwards in incremental and unpredictable shifts. The set-up was simple enough. Taking on the role of initial curator, Naomi Sex nominated the artist Alan James Burns, who nominated another curator, who would subsequently nominate another artist, and so on. This played out until there were three artists and three curators linked in a chain of nominations. While the outcomes of the process were naturally unpredictable, they would eventually come together under the auspices of Sex’s residency on IMMA’S ‘Artists Residency Programme’.

Echo Echo Narcissus Narcissus, Jan Verwoert and Federica Bueti. Photo Fiona Morgan

This account begins with Jan Verwoert and Federica Bueti, the final nominees, and follows the line backwards, to Sarah Pierce who nominated them, to Linda Quinlan who nominated her, and so on, before arriving back at the beginning. There is a greater focus on the artists because I am responding to the available evidence. The backwards arrangement is based on the evidence too, as it begins where the iron staircase led me, turning left into Studio 3A, towards the evening’s first encounter. Echo Echo Narcissus Narcissus was an amalgam of objects and recorded voices recreating, or resuscitating perhaps, a previously live performance by Verwoert and Bueti at the 2014 Liverpool Biennial. (3) Narcissus’s reflecting pool had become a blue stage. It seemed bereft. Meagre props – a metal stand, a loudspeaker covered with a silver lampshade – were completed with a spill of shiny granules, half-hearted confetti, reflecting a pair of feather-appended twigs twirling squeakily overhead.

Originally billed as, “An attempt at inducing mutual metamorphosis with the help of words, echoes, glitter, and a pool”, the living presence of Verwoert and Bueti had been substituted with their recorded voices emanating from the silver shade. (4) This “speaking, reflecting object” may have ‘echoed’ their previous performance but the result was intriguing more than spellbinding, the artifice too deliberately prosaic for any suspension of disbelief. (5) Perhaps the work’s function within 6ix Degrees was to reflect on a certain kind of mutual dependency. In her introductory text Naomi Sex writes about, “… activating the powerful social network existing in the art world”, and thus reminds us, if it were necessary, of how dependent – how reflecting of each other’s gaze – the inhabitants of the art world can be. (6) The studio floor had a dusting of blue glitter, a metaphoric stardust gradually extended into a galaxy by the viewers’ shuffling feet.

Sarah Pierce had nominated Verwoert (who invited Bueti to join him) for 6ix Degrees. Pierce’s umbrella project ‘The Metropolitan Complex’ covers a wide-ranging practice that finds inventive ways of interrogating art without seeking to consign it to determined historical positions. Like Verwoert and Bueti’s ‘special edition’, her work includes reiterations of various kinds. In re-presenting objects and re-staging actions, recent works like Lost Illusions/Illusions perdues and Gag afford echoes and reflections a privileged place. Pierce identifies forms of gathering as a primary interest, and the renegotiation of, “ … gestures, actions and questions of community.” (7) As a member of the evening’s community of viewers I made my way (trailing stardust) across the corridor to Studio 3B.

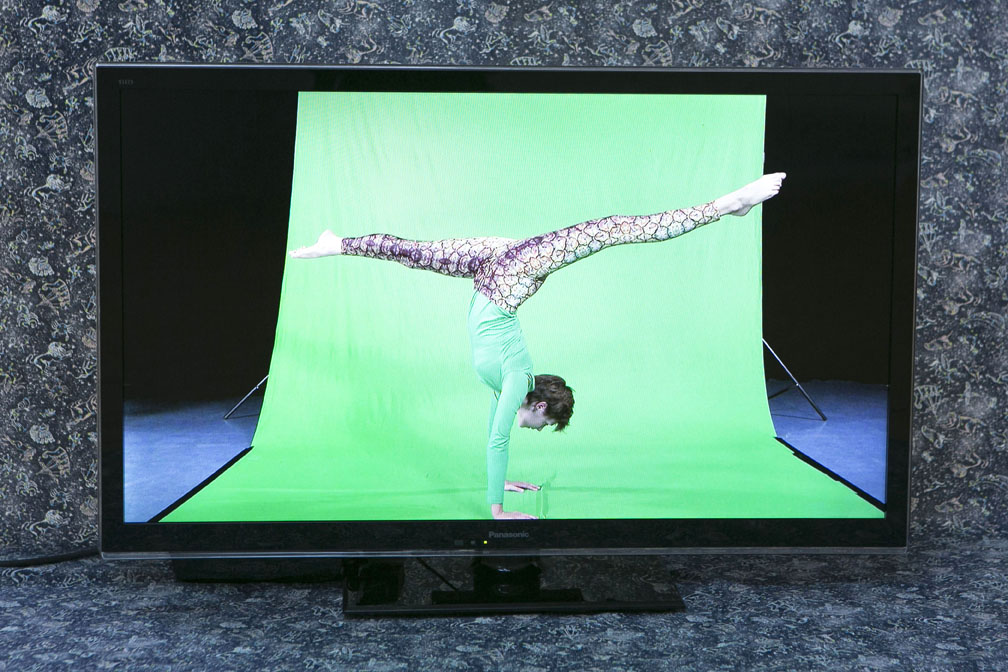

Ananas, 2011, Linda Quinlan. Photo Fiona Morgan

This second, larger space was two thirds empty, while a suspended sheet trailing onto the floor obscured the remainder. Behind this ornately printed fabric a floor-based monitor displayed a studio with a green screen. The seamless set-up of the green screen mirrored the set up of the printed fabric. On screen a female figure performed studied acrobatics, her scissoring legs dressed in the repeating patterns of a pineapple.

Ananas (2011), by Linda Quinlan, continued with an animated sequence that morphed the legs into a machine-like pinchers. Then a slow-moving close-up transformed one extended limb into the body of a snake, its patterned undulations finished off with a telltale rattle. All the while, and on the way to a final image of a municipal looking pond (another reflecting pool) the sounds of a tennis match played out, to and fro. The installation had the feel of a mini encampment, shielding a set of shamanistic images as optically vivid as they were semantically obscure. Quinlan has some previous with the ineffable, with the obscure. Writing about her Galway Arts Centre show, ‘Like Horses and Fog’, (2008) Joseph R. Woolin exhausts his phrase book of pauses and gaps, mentioning, “the irretrievably unknowable”, “aporias of knowledge” and “caesuras in narrative”, to establish a rationale of mystery for Quinlan’s curiously indefinable art. (9)

Coincidently, as a graduate of the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, Quinlan also has some ‘previous’ with Jan Verwoert (He teaches on the MA programme there). Speaking in Glasgow in 2010 Verwoert critised some older art practices for being too readily prescribed, for making what he calls “transparent entries into the history books”. (10) He gives examples of alternative strategies characterised by indefinable gaps (“caesuras in narrative”, if you like), strategies where, as he puts it, “… there is something different in the moment of production that cannot be entirely mapped onto the moment of reception”. (11) Quinlan’s beguiling, eccentric registrations, of form and content, images and sounds, might serve to illustrate his point.

While Quinlan had nominated Pierce, she was herself nominated by curator and writer Marysia Wieckiewicz-Carroll. Marysia and I fell into step on the way to the studios and experienced Quinlan’s second work together. An audio loop of an intermittent birdcall, ‘E’ sounded unexpectedly from somewhere overhead. Marysia noticed me noticing it though I didn’t realise I’d noticed it at all. Perhaps discursive projects such as Sleepwalkers and (((O))) have honed this intuition. Wieckiewicz-Carroll was a co-curator on Sleepwalkers, an investigative art project (brainchild of Michael Dempsey at the Dublin City Gallery: The Hugh Lane) that emphasized the value of shared enquires over singular outcomes. (12) While Sleepwalkers was eventually manifested in a series of publications and exhibitions at the Hugh Lane Gallery, the discursive project – ‘(((O)))’ – resides primarily in the ether. A loose assembly of artists and activities overseen by Lee Welch (another Sleepwalker) and Teresa Gillespie, guests were invited to “ … affect and expand its resonance” through open-ended dialogue. (13)

(I am writing this the morning after hearing Peter Brotzmann play at the National Concert Hall. Brotzmann wields his saxophone like an assault weapon and his opinions can be pretty direct too. I’m reminded of a ‘Wire’ interview where he mused, “If you want your own space and your own time you have to fight. Nowadays they talk about dialogue or creating a space, but you know, that’s why it’s all so fucking boring”). (14)

Alan-James Burns. Photo Fiona Morgan

Maybe dialogue can be overdone – and these days it receives a superficial impetus from the ubiquitous ‘share’ button – but when shared experience is inevitable why not talk about it? By 4.30 pm the room was full of people talking. By 4.30 pm people talking was the main event. Then, seemingly casually, the dialogue stopped and a more one-sided form of sharing began. Alan-James Burns’ scheduled but unannounced performance started with the artist saying how nervous he felt, and it took me a moment – I admit it – to realize his ‘nervousness’ was part of the act. This performance of nerves sat oddly with his actual nerves, creating an uncomfortable overlap, or to paraphrase Jan Verwoert, the moment of production was uncomfortably mapped onto the moment of reception. The simultaneity of these moments (peculiar to performance art) allowed an awkward but fascinating access to Burns’ slippery words and thoughts.

While the performance benefitted from being alive in the moment, to effectively perform a stream of consciousness you either have to make it up on the spot or write, rehearse, and deliver the material so seamlessly that the audience is prepared to go with the flow without questioning it. Following a line of thought that was equally self-reflective and self-conscious, Burns’ prepared monologue ran along side my own interior one, a simultaneous questioning that wondered if he could up the ante by adding speculation about his audience (whoever they may be) to his narrative, charging the experience with something more nervy and complex. If Burns’ monologue was more off the cuff, or more self-assured, would it have been better? Maybe. Though his performance lacked polish his genuine awkwardness added a compelling and necessary tension.

Burns’ stand-up (performed on the edge of his seat) had the oxymoronic quality of a comedy routine without punch lines. A comedian provokes behaviour (laughter, hopefully) but Burns seems more interested in investigation and analysis than with cause and effect. This desire to uncover from within is also important in Naomi Sex’s practice. She has harnessed the monological structure too, but where Burns’ words present a tailored version of him, her scripted monologues employ actors to make her words more detached. (15)

The ‘about’ page on Sex’s website ‘performs’ this detachment by refusing to be subjective when outlining aspects of her own approach, “… you use the performative lecture as a formal device to reveal and articulate the informal, the veiled, the intangible, …” . (16) Sex’s practice is concerned with examining the often hidden and sometimes rigidly hierarchical structures that support art practices. She attempts to do this from the inside, manipulating and uncovering methodologies through her own artistic interventions. Hers is not a knowing stance however; she is not trying to expose the workings of a system in order to debunk it. Instead, and projects like 6ix Degrees are stimulating evidence of this, she set things in motion with a deceptive insouciance, hoping to be surprised more than validated by the outcomes.

By 7pm the evening’s moving parts were winding down. People leaving, speakers unplugged, monitors going dark in the dark. A festive cable led from the studios to the Flanker building next door. (17) It had been raining, and the wet courtyard danced beneath the line of lights.

John Graham, 2014

- Karinthy’s story ‘Chains’ appeared in 1929.

- Emphasis added. 6ix Degrees original pdf invite.

- Though ‘artist’ in the context of 6ix Degrees Berlin based Jan Verwoert is primarily known as an art critic and educator. Federica Bueti is principally a critic and researcher.

- http://www.biennial.com/2014/exhibition/the-companion

- 6ix Degrees

- Ibid

- themetropolitancomplex.com – ‘Lost Illusions/Illusions perdues’

- http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/linda-quinlan/

- http://www.gsa.ac.uk/life/gsa-events/events/j/jan-verwoert–why-are-conceptual-artists-painting-again/#jw

- Ibid

- Initiated and overseen by Michael Dempsey at the Hugh Lane, participants included the artists Clodagh Emoe, Jim Ricks, Sean Lynch, Linda Quinlan, Lee Welch and Gavin Murphy, and curators and writers Maysia Wieckiewicz-Carroll and Logan Sisley.

- http://www.clonleastudios.com/ooo/ooo.html

- A legendary exponent of European ‘Free Jazz’, Peter Brotzmann’s second album was called Machine Gun (1968). He played that night in the Kevin Barry room with Irish pianist Paul G Smyth. The quote is from The Wire magazine, November 2012, issue 345

- In 2013 her Synchronised Lecture Series featured simultaneous lectures performed by nine actors in nine educational institutions throughout Ireland.

- http://www.naomi-sex.com

- The Flanker building hosted the after-party.